The Power of Your Small, Ordinary Life

So, you don’t have the flash corner office and the fancy job title. You haven’t written a best-seller or amassed a gazillion Insta followers. Your one TV appearance was as a passer-by in a local news report and your last award was from primary school. In a culture that often measures life by public recognition, it can feel like our small, ordinary lives matter little.

But oh they do.

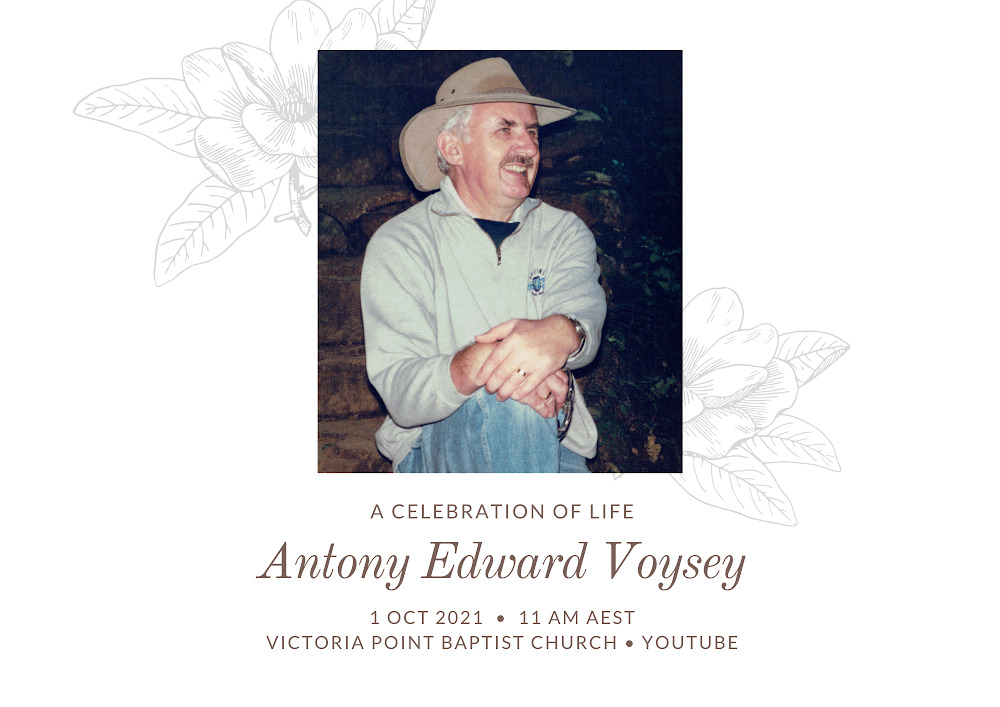

My father had no fame or major awards to his name. But his life mattered. Just ask those whose who attended his funeral—like the pallbearer who broke down recounting the impact Dad had on him and his faith, or the old workmates who told stories of a man of integrity, curtesy and fun, or locals from the community who spontaneously got up to pay him tribute. I had the honour of giving the eulogy at that funeral. I share it here (or you can watch it below) because it’s a reminder that in the end our lives won’t be measured by corner offices or Instagram numbers, but by our love. And love is revealed in the stories those closest to us tell of us.

Dad’s life was like yours and mine, seemingly small and ordinary. But it mattered.

And ours do too.

A Eulogy for Dad

Reflecting on my father’s life, it’s surprising to me that one of the dominant images coming to mind is of a garage. Specifically, the garage of my childhood home in Cleveland, Brisbane. With the roller door up you’d see it was barely wide enough to house our old Ford Cortina, and squeezing between the car and the left-hand wall with its shelves of nuts, bolts and WD40 cans, you’d get to a small lino-covered area at the back—with a table on the right littered with electronic components and wire. At that table, sitting on tall 1970s-style kitchen stools, Dad would teach me how to use a soldering iron and we would build Dick Smith kits and make our own stereo systems. I can smell the burning solder now.

On a Saturday morning Dad would roll the Cortina down the driveway and onto the road, giving us more room to work. Those were the happy days when you could bring home as much from the rubbish dump as you took. And we did—every trip to the tip yielding a broken model plane, toy car or bicycle frame. My favourite find was a wooden go-cart which had a lawn mower handle for a frame. On that garage floor we gave it new wheels, attached a sporty plastic windscreen, and with Dad standing on the corner watching out for cars, I’d race down the driveway clutching the steering rope for grim life, skidding left into our street then right into the next, with a rush of excitement any crashes and cuts could never kill.

There seemed nothing my Dad couldn’t do back then. He and Mum had built that childhood home themselves, putting up walls, laying pavers, erecting fences and building fancy brick mail boxes for the front yard. When industrial action led to rolling blackouts in the 1980s, Dad set up a bank of car batteries in the garage connected to a string of emergency lights through the house—when the power cut out, the emergency lights switched on. I thought that was clever. Not all his inventions were so successful, though. The Tony Voysey Solar Hot Water System made of coiled black tubing on the roof never actually made water hot, and the Tony Voysey Letter Detector—made of lasers, sensors and a stop-go traffic light system—never did save us the arduous ten-second walk to the mail box.

But that doesn’t matter now. Because whether what was made worked or didn’t, whether sitting on those kitchen stools soldering wires or getting down on our knees fixing go-carts, a young boy was being shaped by the presence of his dad. And with its musty solder-smoke smells and its memories of battery banks and WD40 cans, that garage will always be a symbol to me of my clever father’s inventiveness.

A second image that’s come to mind has also been unexpected. It’s of a car. No specific car this time, it just seems that many of my important memories of Dad involve one—from him picking up 12-year-old me from Thursday night skating at the Rollercade, to him driving 17-year-old me to Fortitude Valley each morning for my first job out of school. Thirty years on, one of those memories still brings a sting of embarrassment.

It was somewhere around 1990. I was 18 and spending many a Friday night in Brisbane’s nightclubs, learning how to be a DJ. I now owned that old Ford Cortina but didn’t have a licence to drive it, so getting home required me catching the last train to Cleveland from Central Station at 12.55am. There were many close shaves running through the city at 12.54am. I guess it was only a matter of time until I lost the gamble.

And I did. One morning I raced down the escalators in time to see the last Cleveland train pulling away from the platform. I stood there panting, the horror of my situation sinking in. There were no more trains for another five hours, no buses, I had no money for a taxi, and no stomach for sleeping under a bridge. I dragged my heels to a pay phone and made the phone call of death.

Dad answered the phone, groggy from sleep. “Hello?”

“Hi Dad. I missed my train. Can you pick me up?”

He muttered something unintelligible and hung up. An hour later he pulled up outside Central Station and I sheepishly got in. He smiled and said, “Who’s a drongo, then?” I said I was, and we drove home. I was grateful for his forgiveness.

For some reason he wasn’t so forgiving when I did it again the next week.

A car plays a special role in my family’s very formation. Apparently Dad first locked eyes on my Mum at a party in London. He gate-crashed a second party to see her again, then organised a third hoping a mutual friend would invite her along. After that, Dad arranged a group dinner at a country pub but was so nervous about seeing Mum he got a migraine and couldn’t eat a thing. Finally came a country drive with just the two of them—in Dad’s 1950’s model Rover. That car was Dad’s pride and joy. Lacking a heater, he’d put his soldering iron to work and put a red light in the glove box to provide at least some emotional warmth. Who knows if it was his charms or the car’s, but from then on Tony and Vivienne were sweethearts.

But there was a snag. Mum was about to move to New York to study, and then to Peru to become a missionary. Dad saw Mum off at the airport. The letters he sent while she was in New York fended off her other suitors, and five months after she arrived in Peru, Dad arrived too—whisking her to the top of Machu Piccu to propose.

He’d paid for the plane ticket by selling his beloved Rover.

Dad never went to university, although he’d have easily made it to Oxford (or Cambridge if he was desperate). He won a scholarship to Dulwich College—a prestigious boys school in London that produced graduates like Sir Ernest Shackleton. He quickly rose through the ranks at publishers Chateau and Windus, and Angus and Robertson. When he sat the entrance exam for what is now Telstra, he came joint first out of two-hundred applicants. He was good at brain teaser puzzles—a talent he passed to neither of his sons. On his first visit to a shooting range, staff watched in awe as he hit bullseye after bullseye. Dad was sharp-eyed, bright-minded, smart.

But university and publishing careers couldn’t be a priority when the world was about to end. That’s what his religious leaders told him back then. And so Dad became a missionary in various parts of England instead, knocking on doors hoping to save anyone who’d listen before Armageddon came.

Some of you already know about my parents’ time in the mind-controlling religion that is the Watchtower Society. The full story of their breaking free is long and wondrous, and for another day. On the up side, that religion brought Mum and Dad together and produced me and my brother Tristan. On the down side, it led to spiritual torment that at times affected their mental health, and later resulted in ostracism from their family and friends. For a decade they didn’t know what to believe, fearing that they, Tristan and I would be the ones lost at Armageddon. But thanks to the long-term prayers of a few, a two-year quest by Mum to find out the truth of Jesus’ deity, and the wonder-working power of God, they found the freedom they were looking for. One day in 1990 Dad found himself taking communion for the first time at what was then a tiny church called Victoria Point Baptist. After nine important years growing and serving at Cleveland Baptist, and another nine at Gateway Baptist, these last six years at Victoria Point have been a special return to a place that’s played a significant part in their spiritual journey.

Which leads to a final car memory.

Dad and I were driving to work one morning in 1991. Dad looked out at the traffic and said, “Look at these people! They think they’re happy but they don’t know what real happiness is!” Dad was full of the joy of God—a joy that never left him, even during the pancreatic cancer he faced and the other health challenges he and Mum both faced; a joy he shared with the many confused people who’d visit over the years, limping from their own wounds from mind-controlling religion; a joy he’d share with nurses and doctors in the hospital wards, and one which led him to have no fear of death—his sins forgiven, his place in eternity secure, convinced that:

… neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, can separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Romans 8:38-39

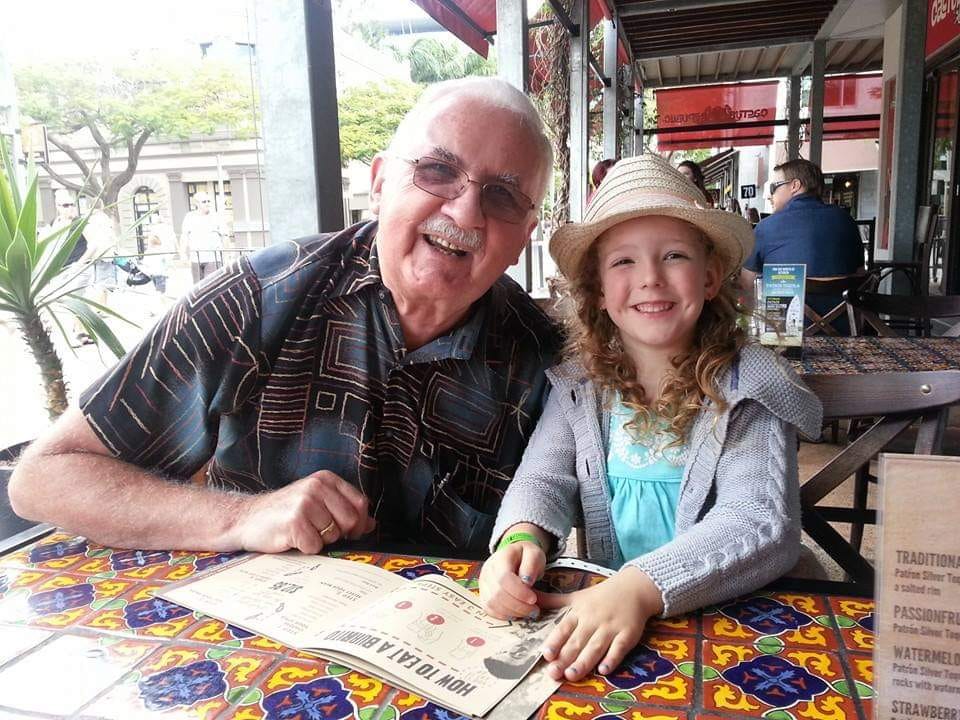

It seems I’m not the only one with memories of Dad, garages and cars. On their last visit to Cleveland before the border closed, my brother and his family pulled into Mum and Dad’s driveway to find Dad sitting in the garage on a camp chair with the door up, waiting for them to arrive.

Dad taught us things and took us places. He was my chief cheerleader, listening to every interview I did, downloading every talk I gave, proof reading every book I wrote, always ready to say how proud he was of us all.

He was sharp-eyed, bright-minded, inventive, joyful, kind.

And I can’t help thinking that when our own final day comes, Dad will be there on a camp chair with the door up, waiting for us.

Bye for now, Dad.

Watch

More

Listen to Sheridan speak about this on BBC Radio 2’s Zoe Ball Breakfast Show

Antony Smith

I found this very moving, Sheridan. A beautiful tribute to your Dad and a timely reminder of what is important in life. My sincere condolences. My own father is currently undergoing tests for pancreatic cancer in Guildford, UK, while I sit thousands of miles away in Brisbane hoping for the best, but fearing the worst. Covid and border closures are making a tough situation that much harder, a situation I imagine you can relate to. Thank you for sharing your experience. I’m very sorry for your loss. May your father rest in peace and rise in glory.

Sheridan Voysey

Oh Antony, our situations are the same but just geographically reversed. Wretched Covid closures. Zoom/Skype/Messenger video calls are an absolute lifeline until Queensland opens again (which is hopefully not too far away). And if there is a diagnosis, do know that the drugs available today can manage things so much better than ever before. I’m praying for you today.

Lyn Wake

What a stunning tribute to your dad Sheridan – thank you for sharing. Our love and prayers are with you as you grieve with hope.

Sheridan Voysey

Thank you so much, Lyn. You know all about that road of grief and hope.

Tracey Smith

This is beautiful Sheridan. It got me when you shared that he sold his car to buy the ticket to Peru – and then again, waiting with the garage door up. What a wonderful father.

Sheridan Voysey

Indeed he was. Thank you Tracey.

Maureen Watson

What an amazing and moving tribute to your lovely father Sheridan. My thoughts and prayers to you all. Thank you for sharing, and may God be really close to all the family at this time.

Sheridan Voysey

Thank you o much, Maureen.

Celeste

May the Lord Himself wrap you and your family in His arms as you grieve, and yet celebrate, Sheridan. Your dad’s garage has come alive to us who know you only through the electronic medium. We can feel the air, hear the sounds and imagine the lights of those moments made by a creative and innovative dad. Nothing ordinary about him- but everything extraordinary.

Blessings to you and the comfort that surpasses all comfort through Him who gives you strength.

Thank you for sharing.

Celeste

Sheridan Voysey

Thank you for such lovely words.

David

Thanks for sharing this. My Father passed away 8 years ago today and this jogged some happy memories of him.

Sheridan Voysey

Someone told me the memories that sting now would bring joy later, so I’m glad to hear that’s true for you. Thanks David.

Mona

Thank you so much for sharing. My Deepest Condolences to you and your entire family. May your Dad’s soul RIP!

Sheridan Voysey

Thank you, Mona.

Angela Seneviratne

Am so grateful to have read your note and your Eulogy for your Dad. Yes I agree with you that people matter regardless of what the world thinks as important. Reading your story about what your Dad was to you and your mum and bro shows the world how important it is for us to show up and be there and take some risks, not judge! May your Dad’s memory be celebrated through all the lives he has touched and may his legacy live on.

May he rest in peace and rise in glory.

Sheridan Voysey

Amen. Thank you.

Diane Fopp

Thankyou so much for this reminder of what is important and to be valued, Sheridan. Often it is just so easy to be carried away by the world view and we lose sight of the many simple blessings we enjoy each day. My sincere condolences to you and your family. Thankyou for sharing so honestly.

Sheridan Voysey

It sure is easy to lose that focus. Thanks so much, Diane.

Michelle Vergara

Thank you for sharing your Dad — and your delight and love for your Dad — with me. His “ordinary” life is encouragement to me in mine. Keeping you and your family close to my heart in prayer.

Sheridan Voysey

Thank you, Michelle. That is so appreciated.

david glyn strange

Thanks Sheridan, what a wonderful tribute to your dad. Tony was fortunate to be surrounded by a loving wife and children. Your true appreciation of God’s love shines through.

Sheridan Voysey

Thanks so much, David. I appreciate that.