Anne Rice: Christianity’s Outsider Once More

As many a good fiction writer knows, there is often a deep, mysterious and symbolic link between an author’s life and the books they create. Unconscious wells are tapped as words are chosen, sentences crafted and metaphors made. Only later does a writer realise how much she or he was the real character of the story.

Such may be the case for Anne Rice, the queen of dark novels like Interview with the Vampire and other gothic tales. For Rice, the vampire was deployed as a metaphor for the outcast: the soul disconnected from others, from meaning and from hope. Her own story is in many ways analogous, its latest twist making her once more an outsider.

Online literary and religious worlds have been aflutter after Rice’s recent announcement of her quitting Christianity. ‘Today I quit being a Christian,’ she posted on her Facebook page on July 28. ‘I’m out. I remain committed to Christ as always but not to being “Christian” or to being part of Christianity.’ A following post stated the reasons for her stand. ‘I refuse to be anti-gay. I refuse to be anti-feminist. I refuse to be anti-artificial birth control. I refuse to be anti-Democrat. I refuse to be anti-secular humanism. I refuse to be anti-science. I refuse to be anti-life. In the name of Christ, I quit Christianity and being Christian. Amen.’

Rice’s uneasiness with organised religion has been growing for some time. In her 2008 memoir Called Out of Darkness, she admitted to some disagreement with her Catholic denomination over issues like gay marriage and abortion laws. In a recent National Public Radio interview Rice explained that the final straw for her was the decision of California’s Catholic bishops to back Proposition 8, the bill opposed to the legalisation of same-sex marriage in that state. In a CNN interview Rice also deplored the comments of church leaders who linked the September 11 attacks to the ‘evils’ of homosexuality and radical feminism. Though her faith in Christ is still “central” to her life, according to a July 29 Facebook post, Rice has removed herself from the Christian world as an act of conscience.

Rice started life within the church. Reared in a strict and sheltered Catholic environment, she participated in Mass regularly and had a Catholic schooling. But any early faith was abandoned at the age of eighteen when religion proved to be a barrier, in her mind, to the free thinking her college education was offering. ‘I made the mistake of thinking that I had to abandon my religion to go out and discover what existentialism was and what the modern world really was,’ she told me during a radio interview in September 2008. ‘I made the mistake of thinking that I couldn’t talk to God about the doubts I had and the questions I had.’ Her prayers stopped, her doubts solidified and atheism became her creed.

Now free of religious restriction, Rice’s subsequent writing career proved her status as Christianity’s outcast. Interview with the Vampire was released in 1976, the first of the highly successful Vampire Chronicles series, and was later adapted into the popular film starring Tom Cruise and Kirsten Dunst. Vampires, witches, gender-bending romances and bondage-ridden erotic novels (under the pseudonyms of Anne Rampling and AN Roquelaure) became her fare. Anne Rice became an overwhelmingly successful author. Her book sales today approach the 100 million mark.

Yet, amidst the fame, money and success, Rice lived with an unmovable sense of despair—a despair that seeped into the Vampire Chronicles novels. ‘There is a protest going on in those books,’ she said to me. ‘Lestat and Louie and Armand—the vampire heroes and heroines in those books—they protest, they shake their fist at the night and say “we want to find some meaning”. It’s me sort of having a fight with myself.’ The clearest depiction of this inner turmoil she says was her 1995 book Memnoch the Devil through which she was desperately asking spiritual questions. ‘Of course, it ends sadly and tragically because I didn’t have the answers yet. But I think it is the most rich of all the books that I wrote and possibly the one that goes the farthest in knocking on the door and begging the Lord to let me back in, even though I didn’t know that’s what I was doing when I wrote it.’

During our interview Rice defined the vampire as her symbol of one who has ‘lost faith and lost any promise of eternity… doomed to go on in the darkness, looking, searching, hoping.’ Lestat and Rice were now discovered to be one: both outcasts stumbling in the dark, in search of some kind of redemption.

That redemption came, according to Rice, in her much talked about re-discovery of Christianity. Her inner longing sent her on a quest which led her back to faith. ‘I kept asking myself what Christianity was about. How did it start? How did it manage to take over the whole Roman Empire? How did the Jews manage to survive all these centuries? I began to be plagued by these questions and I realised that I was obsessed with these questions because I had never stopped loving God. I had told myself I couldn’t believe in him, but I had never stopped loving him. And I saw God everywhere that I looked.’ On one Sunday afternoon in the late 1990s, Rice asked her Catholic secretary if she could arrange for her to see a priest and talk about returning to the Catholic Church. A meeting was organised, a two-hour confession followed, and the outcast was later welcomed home into the faith of her childhood.

The impact of that decision should not be underestimated. In 2002, while sitting in church, Rice dedicated the rest of her writing career to Christ. ‘If I didn’t have the courage to be Mother Teresa, if I didn’t have the courage to give away all I possessed and go follow him, I could give him all that I did—I could give him all my work,’ she told me. ‘I was never going to write anything again that didn’t reflect my faith in Christ.’ This was no small feat considering her success. Would her many fans cast her away? One result of Rice’s decision was her Christ The Lord series of books (incorporating Out of Egypt and The Road to Cana

to date), fictionalising the life of Jesus. The two volumes published so far contain some of the most beautiful portrayals of the Nazarene you will find.

But now a new turn has been taken in the Anne Rice plot with her walking away from organised Christianity. She has left not just the Catholic Church but Christianity altogether, she has said on her Facebook page. ‘For ten years, I’ve tried [to remain]’, she posted on July 28. ‘I’ve failed. I’m an outsider.’

An outsider.

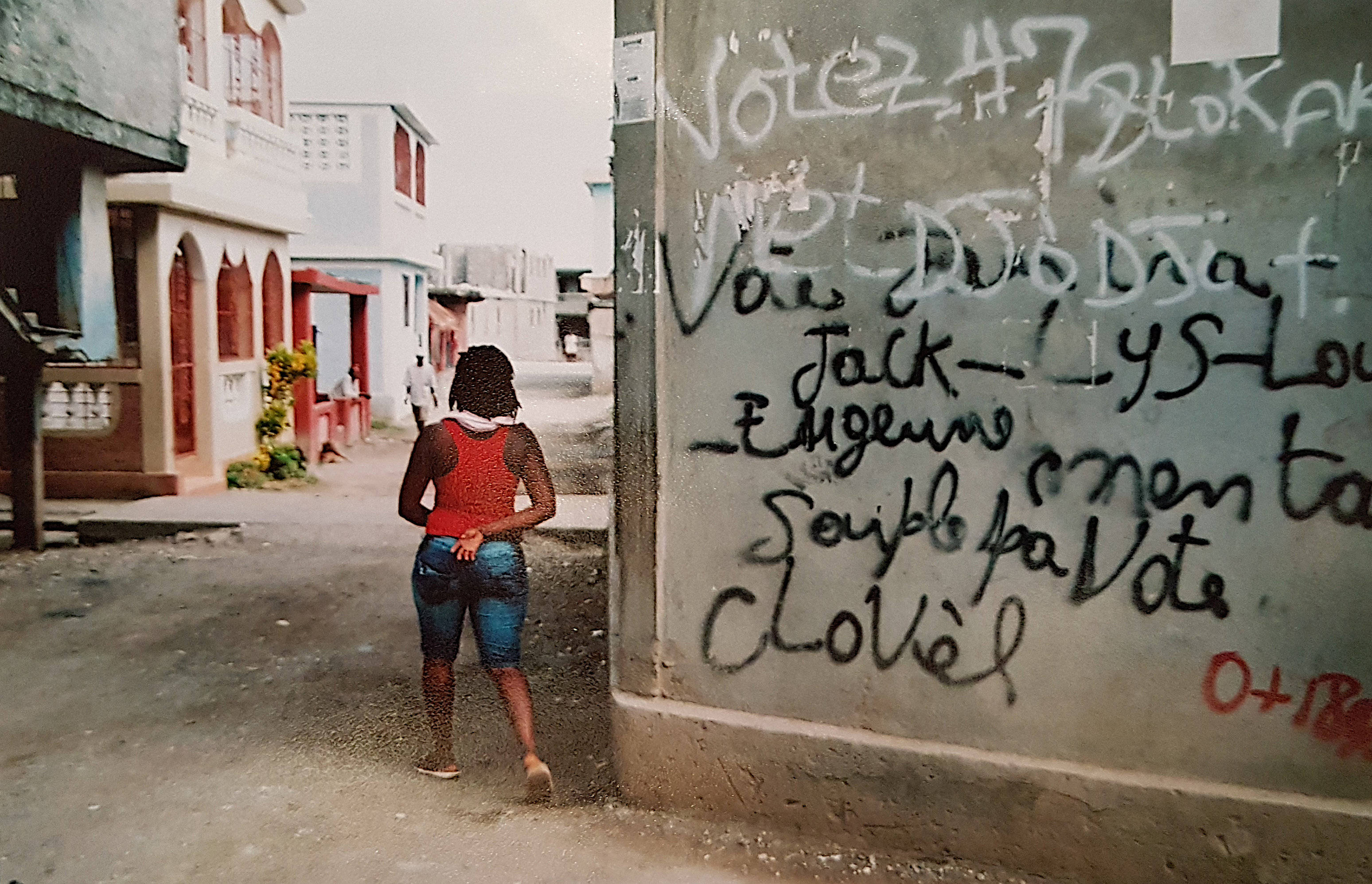

A sense of the familiar wafts into Rice’s story here. Outcast language is found in other announcements from Rice also. ‘I have to step into the wilderness,’ she told CNN. ‘I have to talk to God personally and seek his guidance for what he wants me to do to keep Christ as the centre of my life.’ Once the outcast, then returned, Rice is the estranged one once again, heading off to the wilderness, albeit this time with God.

Rice’s public stand against the churches of her country has generated plenty of talk in the US media and blogosphere. Her Facebook page has been showered with congratulatory remarks from fans fed up with hypocritical religion. Today’s church is far from Christ, they declare. There are strong grounds, of course, for such sentiment.

Some have felt it unfair to blacken an entire faith by the actions of a few. Not all Christians in the US are anti-gay, anti-science or anti-Democrat, people have said. There’s truth here also. Rice herself has been overwhelmed by the generosity shown to her by journalists, bloggers and the public after her announcement. Ironically, many of these generous words have been written by the very group she’s denounced—the Christians.

Others have counselled Rice to consider the cost of Christian discipleship. Jesus said his pathway was narrow and required a personal cross to be carried all the way along it. When true to Christ, Christianity will often be at odds with the prevailing culture in at least some areas of morality and ethics, with defiance costing his followers dearly. The Gospels give this viewpoint merit too.

What hasn’t been pointed out is that Rice’s story has not reached its final chapter. Many saints and sinners have had their moments of doubt and defiance, abandoning the community of faith to wander into wilderness. For the Jews of Old Testament times the wilderness represented vulnerability: their Egyptian Exodus was a journey through rough terrain in unknown land with only the promises of God to sustain them. But the wilderness was also a place of transition too. Those Exodus wanderings defined the Jews as a race and as the people of God. Jesus the Jew spent forty days in the wilderness before heading back to Galilee and changing history.

Anne Rice may be Christianity’s outsider once more but this wilderness period may prove her defining point. The story isn’t over—we are still a few chapters from the end. As such, her journey is symbolic for all who would investigate the things of God. A time comes when one must decide what one believes and where one’s allegiance lies. And that always requires a little wilderness time.

This article first appeared on ABC Religion and Ethics. The full transcript of my interview with Anne Rice can be found in Open House Volume 2.